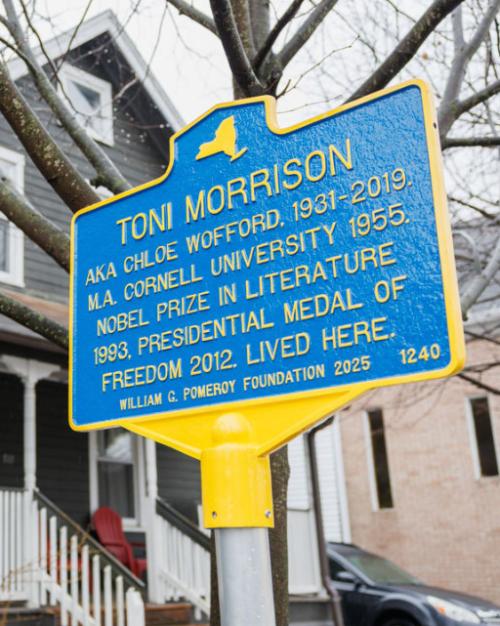

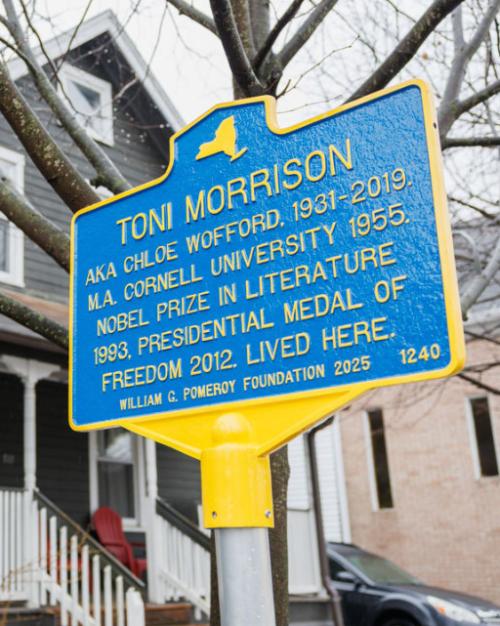

Historical marker commemorates Toni Morrison’s time in Ithaca

Cornell Chronicle

Department Homepage

The College of Arts & Sciences

Department Homepage

The College of Arts & Sciences